(Part 2 is occasioned by chapter 4 and onwards. You can read part 1 here.)

- A reader asked of the last post “what exactly do you and Sandel mean by this “meritocracy” you are critiquing? You’ve said you’re not opposed to the idea that the best person for the job should generally get that job, so in what sense are you not meritocrats?” That’s a great question. Sandel doesn’t quite spell out what he means by meritocracy, but I think there are a few separable but related theses, viz: A) Meritocracy as a theory of desert- people deserve remuneration corresponding to the degree of contribution their talent allows B) A theory of political priorities- the most important thing is to ensure “equality of opportunity”. Making sure that people at the bottom have a decent life is of secondary importance (if even that). C) A mode of rhetoric, focusing on equality of opportunity, the virtues of rule by the smart etc. D) A willingness to concentrate honor and dignity in hands of the “meritorious” e.g. talented. E) A theory of how political problems arise, viz not having the “best people” with the “smartest ideas” take care of them- instead of conflicts of value, practical interests and moral beliefs. Hence meritocrats find themselves committed to what I and Scott Alexander have previously called “Mistake theory” and contrasted with “conflict theory”.

- Sandel makes a big deal out of what he calls “smart language”, especially the language of “smart ideas” and “smart policies.” Such language is attractive during a period of political polarization where debates over what is right can seem so much more intractable than debates over what is clever, but the solution is a false one. Calling your policies the smart ones insults the intelligence of your interlocutor. What started as an attempt to avoid rancour feeds into it. This is a great point about mistake theories of political conflict generally- in trying to avoid conflict they risk inflaming it by implying that one’s opponents just aren’t as clever!

- Through analysis of rhetoric Sandel argues that the Obama era was a great time for mistake theory (although he doesn’t use the term of course). However, Sandel also makes the point that if mistake theory was dominant during the Obama era as a mode of rhetoric and form of ideology that doesn’t mean it was any truer as an analysis of the political conditions. Rather, constantly talking about “solving problems” “commonsense solutions” “smart solutions” etc. may have predominated precisely because politics was a morass of endless bickering at the time. The mistake theory rhetoric was wishful thinking and/or a futile effort at peace making.

- One of Sandel’s more insightful points is: the obvious unfairness of unmeritocratic societies at least gave a “handle” that social critics and popular movements could grasp onto in an attempt to fight for a better world and better conditions for the lower classes. Critics could say “you have more than me and that’s arbitary, give me more” and there could be a conflict over that demand. Meritocratic societies on the other hand are “frictionless” in a way which doesn’t dissipate popular anger, but instead leaves it inchoate- and potentially more destructive. Just because the apparent “fairness” of the system compared with overt aristocracy (not that the system really is fair, even on its own terms) makes articulating anger harder, doesn’t make the anger go away.

- One of the most important points of the book is that people are, now more than ever before, concerned as much with the distribution of honor as with resources. This is something that, sad to say, I think the left has often gotten wrong historically. People are as worried about getting their lives to fit a meaningful narrative in which they matter as they are about making sure they’ll always have food to put on the table. This may seem like a very obvious point- and surely on some level we all know it- yet I must admit that I’ve often failed to fully get it. Articulating a form of historical materialism which is fully alive to this need is important.

- Sandel discusses the history of meritocracy at length. Two things that stood out especially to me in his discussion. 1. Meritocracy may have been a cold war innovation- a desperate society turning away from entrenched privilege to ensure the best and the brightest would be in place to fight communism. 2. A president of Harvard who was one of the original champions of meritocracy, and insisted it was distinct from equality of outcome, nonetheless couldn’t prevent massive favoritism towards legacy admissions precisely because the alumni were rich and powerful enough to get their own way. This is a superb example of how massive inequality of outcome will tend to eat away at equality of opportunity- whatever noble intentions to keep them separate.

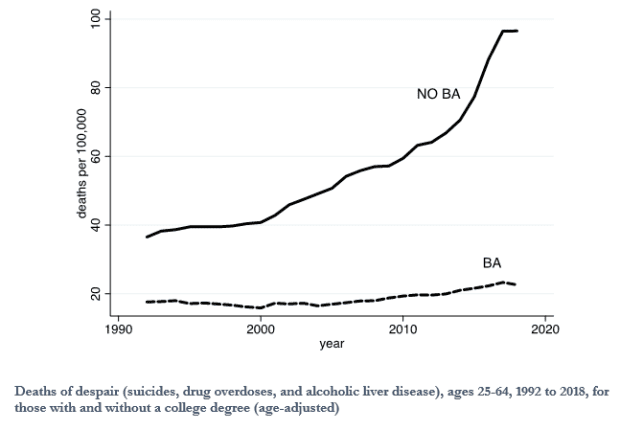

- Sandel reminds us of Erica Scharrer’s fascinating studies of inept men in sticoms. Over time there has been a tendency portray men as more foolish- bumbling etc. in sitcoms, and women as competent and holding the family together. However the impact has fallen unevenly, with working class fathers much more likely to be portrayed as incompetent and useless and the tendency has been increasing overtime. This, suggests Sandel in conjunction with a variety of other evidence is part of a pervasive cultural denigration of all those without a college degree, but perhaps especially men without a college degree. Sandel even suggests that the massive spike in deaths of despair among people- especially men- without a college degree may be linked to this general cultural denigration.

- This ties into something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. One argument we often see on the left is that it’s okay to casually tease men, engage in joking (and even not so joking) misandry etc. because men aren’t an oppressed group. Now there’s a lot of truth to this, but it neglects another truth- when you attack a group, the brunt of that attack will fall on the weakest and most marginalized members of that group. Rich and powerful men will laugh off criticism of men in general. The people who get hit will be poorer, lower status men. The same is true of attempts to “discipline” the bad behavior of men or other dominant groups. The more powerful members of the group will evade discipline, and it will instead fall upon the less powerful members- poorer, more likely to be disabled etc. A more sophisticated approach to social structure is required!

- An extreme example of how “castigation of the privileged” can harm the vulnerable- those people who thoughtlessly say things things like “I can’t understand white men who still end up homeless, you had everything going for you and you still failed”. A disgraceful sentiment.

- Sandel argues there has been too much emphasis placed on distributive justice, when really we should be equally interested in contributive justice. Everyone wants to feel like they are making a contribution to society. At least at the margin, people’s most pressing unfulfilled desires are often not about consumption, but about feeling like they are making a valuable contribution to society. A lot of why inequality stings is not because it means we can consume less, it’s because society is quantifiably scorning our contribution. An ethic of competitive meritocracy doesn’t make the losers feel like their contribution is very significant. Politicians, economists and political philosophers alike have been guilty of making people’s identities as consumers primary over their identity as producers.

- When I think about my own greatest fantasies- to be an acclaimed writer, singer or philosopher, to be a hero, it’s notable that they are all fantasies not of taking from society but of giving to society and of being recognised for that contribution. I don’t think I am unusual in this regard.

- Worth noting that there are resources within my broad tradition- Marxism- for recognising and addressing exactly this point. The idea of the producer alienated from his product in any number of ways is just as fundamental to Marxism as the idea of material scarcity.

- Contributive justice might be all very good and well as a goal now, but let’s say that AI gets better and better and consequently the value of many people’s labour falls. How can we aspire to give everyone contributive justice under those conditions? Sandel doesn’t grapple with this problem, but I think it’s an interesting one. Let’s say that the transhuman solution of “upgrading” everybody so that they can make a material contribution isn’t viable- at least for a time.

- I think under these conditions the best we could probably do would be to encourage people to see themselves as contributing through actions and ways of being that are inherently meaningful. Joy, friendship, self-discovery, making art. To shift from contribution through the production of extrinsically valuable goods to contribution through the “”””production”””” of intrinsically valuable goods. Another good that people can provide that doesn’t necessarily depend on skilfulness is giving their own preferences about what is ultimately, non-instrumentally good in democratic deliberation. I’m not saying it will be easy, but I think there could be a path to give people a sense of making a meaningful contribution even in a post-scarcity society.

- One thought of Sandel’s that will stick with me- the writing is in the wall for neoliberalism as currently understood. Even its most ardent supporters should be able to reocognise this by now. The question then is not will the present “mode” of capitalism fall apart, but what will replace it? Authoritarian centralism? Quasi-feudalism? A replay of the post-war years with renewed unions? War and barbarism? Literal fascism? Social democracy? Socialism? I don’t know if the future is open, but it is certainly unknown. All we know is that the present won’t last. Understanding that the tower is going to fall, we just don’t know which way yet, is an important shift in perspective.

Want meritorious content? You can join our email list here: https://forms.gle/TaQA3BN5w3rgpyqeA and join our subreddit here: https://www.reddit.com/r/dePonySum/

I sympathize with this piece a lot; just wanted to note a case study from the past. I grew up in the Soviet Union and the deliberate praising of the production efforts of the “ordinary people”, e.g. those without higher education, was very visible all the time. News sources covered the heroic work accomplishments of farm and factory staff, there were competitions of the best milkers of cows etc. And yet people looked up to doctors, scientists and writers (who usually weren’t making a lot of money but still) like everywhere else, and the cow-milking contests were a well-appreciated fodder for humor and jokes. What I want to say is I’m afraid that these deliberate efforts to raise the perceived status of “the ordinary man” may work a little but not a lot, the most likely reason being that people are hard wired to constantly compare themselves and others in respect to the abilities and accomplishments that are actually hard to have, thereby giving credible (though not perfect) information about the person’s expected “value” as an ally or mate. I think your proposal to emphasize the general good things that a person can do besides their day job may work better than the Soviet approach.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“massive inequality of outcome will tend to eat away at equality of opportunity- whatever noble intentions to keep them separate.” You make a great point, and it’s probably as important as the “mistake theory” one. You’ve mentioned this idea in a few posts, and it’s something I haven’t heard circulating much out there.

Sam Harris asked Michael about J.K. Rowling, and his response implied that he doesn’t think she deserves all that money, but she certainly deserves our esteem. I think the implication is that merit should still be coupled with esteem but decoupled from money.

Continuing with that, should we then seek equality of esteem?

Also, thank you for mentioning Marxism. Now I understand why I like your site so much. I don’t encounter many writers through the SSC community that come from that angle.

LikeLike

Your point about contributive justice reminded me of G. A. Cohen on the good old days. I don’t think those days are coming back, and I don’t think “the writing is on* the wall” for neoliberalism. Bertrand Russell was certain the status quo of nuclear powers and no world government couldn’t continue, but he was wrong.

Not “in”.

LikeLike

Maybe it’s just that I’m groggy from waking up but I think it’s debatable that Russell didn’t turn out right on that one actually. Eventually the Soviet Union did fall under the weight of a global conflict. Eventually a pax Americana was created that lasted over two decades and was the closest the world has ever been to a single overriding hegemonic government. Would that have happened without nuclear weapons? Debatable but I think not. True, we are now entering a new period of bipolar world relations, but it could be that the pressure of nuclear weapons makes that period shorter than it otherwise would be to. So yeah, I think Russell gets at least partial credit on this one.

LikeLike